Loyalist № 7

To the Peoples of North America, this being a Loyalist response to Federalist No. 10:

Never in the long and noble history of Westminster parliamentary democracy has a governing party collapsed so catastrophically as Canada’s Progressive Conservatives did in the 1993 general election. For nearly a decade, Brian Mulroney commanded national dominance as small-c conservatism gained popularity across the English-speaking world. But then he threw a live grenade to his successor Kim Campbell, resigning the premiership mere weeks before the majority government he had led since 1984 went down in flames. Holding 169 of 295 seats before the writ was dropped, the PCs were reduced to just 2 following the 47-day campaign. Even Campbell lost her own riding – the first and so far only Canadian Prime Minister to be unseated in a general election.

Much of the party’s collapse can be attributed to the rise of two powerful regional challengers. Lucien Bouchard, a former Mulroney cabinet minister, broke with the party over the failure of the Meech Lake Accord and founded the sovereigntist Bloc Québécois. Preston Manning, a longtime critic of Ontario and Québec dominance in the House of Commons, tapped into growing Western alienation to build the populist Reform Party. Fuelled by frustration over failed constitutional reform and a sense of exclusion, both movements transformed regional grievances into organized political factions, shattering the national coalition that had once underpinned Progressive Conservative rule.

The dramatic realignment of Canadian national politics into more of an aggregation of regional interests offers a clear example of James Madison’s concerns about factionalism. In Federalist No. 10, he argues that an essential function of political institutions is to guard against the rise of

[any] number of citizens, whether amounting to a majority or a minority of the whole, who are united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adverse to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community.

Madison feared that such factions, if unchecked, would threaten both liberty and stability by allowing narrow, niche interests to dominate national political life. In Madisonian republicanism, as in the Westminster tradition, democratic stability depends not just on fair competition over policy, but on a shared commitment to the constitutional order. The strength of both political systems lay in their ability to moderate factional impulses through representative institutions. In other words, the durability of any representative democracy – whether an American-style republic or a Westminster parliament – depends on electoral mechanisms that encourage “big tent” politics and the formation of broad-based, national coalitions.

Although he recognized that the formation of factions was inevitable in any free society, Madison believed that their influence could – and indeed must – be restrained. When it came to electing representatives, he argued that smaller constituencies were more likely to fall prey to parochial interests. But “extend the sphere” of a representative’s constituency, he writes,

and you take in a greater variety of parties and interests; you make it less probable that a majority of the whole will have a common motive to invade the rights of other citizens; or if such a common motive exists, it will be more difficult for all who feel it to discover their own strength, and to act in unison with each other.

Madison here observes that the very structure of government either amplifies or dilutes the power of factions, and therefore coalition-building must be incentivized through electoral design. Politics will otherwise be dominated by people who seek only to pursue their own selfish interests at the expense of the common good. And yet neither the Canadian nor the American electoral systems fully succeed in achieving Madison’s prescription for an extended sphere of politics – although for very different reasons.

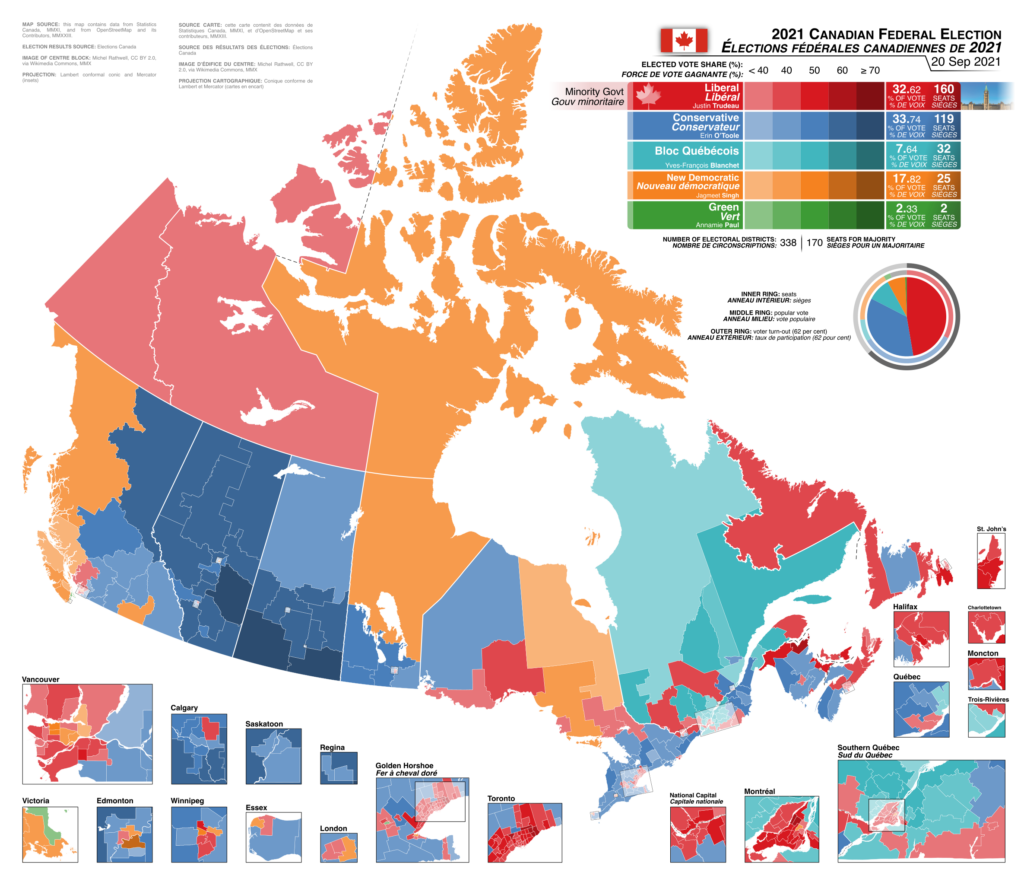

In Canada, the first-past-the-post (FPTP) electoral system demonstrates the dangers that concerned Madison in Federalist No. 10. Rather than encouraging national coalitions, it rewards parties with strong, regional support – even if they have little backing elsewhere in the country. A party can win dozens of seats with only a modest share of the national vote, so long as its support is geographically concentrated. Indeed, in the 1993 election, Canada’s electoral system produced a deep constitutional irony: the anti-federalist, anti-monarchist Bloc Québecois earned the second most number of seats in the House of Commons, allowing it to form Her Majesty’s Loyal Opposition. In every previous Canadian election, that role had fallen to parties that, however adversarial, accepted the legitimacy of the state they sought to govern.

Conversely, a party can win few, if any, seats if its support is widely distributed across the country, as in the case of the Green Party. This distorts representation and empowers factions whose appeal is narrow but intense. And it weakens parties that have wide but shallow support across the country. In other words, FPTP does the exact opposite of what Madison would have had it do: it allows representatives to be elected by a very narrow base, meaning they are likely to become “unduly attached to [local interests], and too little fit to comprehend and pursue great and national objects.”

Because candidates who are elected under FPTP need only gain the most votes – not a majority of them – national elections under a multiparty system like Ours are very often won or lost according to vote efficiency and vote splitting. When parties with similar platforms share the same base of support in a riding, it can allow an altogether different party to be elected to that seat. Ever since the rise of the left-wing New Democratic Party in the 1960s, Liberal leaders who have leaned to the left have always risked conservative competitors forming government, a frequent result that does not accurately reflect the aggregate will of the electorate. Successive governments led by Conservative Prime Minister Stephen Harper between 2006 and 2015, for example, were won largely because of this dynamic.

The American system fares little better, but for altogether different reasons. While Canada’s electoral distortions arise from regional fragmentation, the United States suffers from structural incentives that entrench ideological polarization. Candidates in the United States are chosen through party primaries – a process that places significant power in the hands of a small, and often ideologically motivated, segment of the electorate. Unlike in Canada, where nominees must be closely aligned with the party’s policies and leadership, in the American primary system, factional candidates gain the advantage by appealing more to partisan extremes than to the broader – and more moderate – electorate.

Although general elections in the United States are typically decided by majorities at the district level, the real contest often takes place in the primaries. Of the 435 seats in the House of Representatives, only about 30 are truly competitive; in the roughly 400 remaining safe or largely safe districts, victory in the primary virtually guarantees election to the House. As a result, a tiny sliver of highly motivated partisans can effectively decide who will represent an entire district – and tilt the composition of Congress toward one party or the other. This dynamic is further compounded by closed primaries, which restrict participation to registered party members and make it even more difficult for centrist or coalition-minded candidates to prevail.

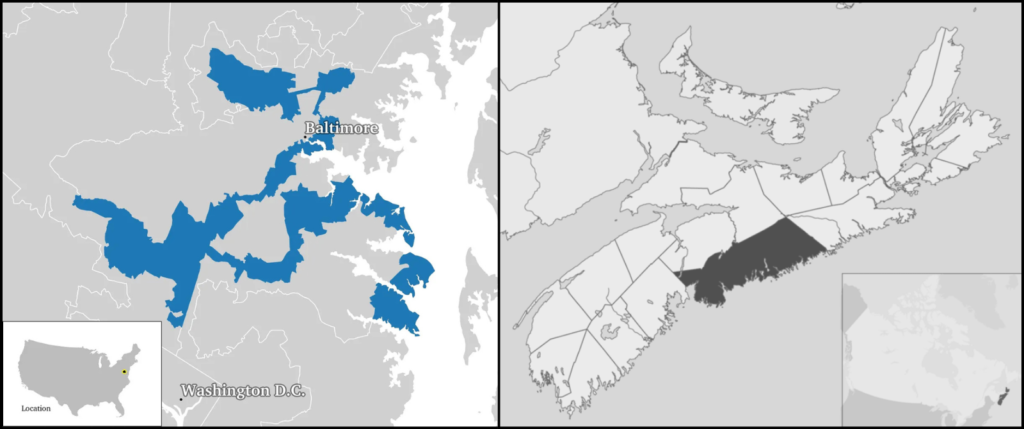

To a very large extent, gerrymandering is the self-reinforcing cause of the problem. In many states, congressional districts are drawn by partisan legislatures with the aim of securing safe seats for the ruling party. This involves a combination of “packing” and “cracking” strategies – concentrating as many party supporters into as many seats as possible while simultaneously diluting the opposing party’s base of support across districts. In this way the ruling party can effectively maximize its own seat count and minimize that of the opposing party – undermining a fair representation of the popular will. Far from expanding the sphere of interest, as Madison envisioned, gerrymandering shrinks it, ensuring that factional interests dominate political life.

Madison believed that, however inevitable the formation of faction in a free society, representative democracy under the U.S Constitution would be able to contain its corrosive effects. “A government in which the scheme of representation takes place,” he wrote in Federalist No. 10, “promises the cure for which we are seeking.” Yet the Madisonian cure is insufficient to guarantee thoughtful moderation. In recent years, elections have repeatedly returned to Congress extremists like Marjorie Taylor Greene and Matt Gaetz – House Republicans who are not only polarizing figures but who reject altogether the Republic’s constitutional framework.

Madison had great faith in the capacity of representative government to elevate reason above passion. Considering the scale not just of the country as it was then, but as he hoped it would become, Madison wrote,

as each representative will be chosen by a greater number of citizens in the large than in the small republic, it will be more difficult for unworthy candidates to practice with success the vicious arts by which elections are too often carried; and the suffrages of the people being more free, will be more likely to centre in men who possess the most attractive merit and the most diffusive and established characters.

Not exactly. Creeping factionalism both in the United States, particularly in the Republican party, and regional fragmentation in Canada, particularly in the prairies and in Québec, cast doubt on Madison’s optimistic vision of peoples in North America who are able to govern themselves wisely. Whether under the Stars and Stripes or under the Crown, Our democratic institutions are weakening under the strain of hyperpartisanship and regional grievance.

These trends carry with them a dangerous impulse: to treat disagreement not as an essential feature of democratic life, but as something illegitimate. Yet dissent is not treason – to insist otherwise is to reject the crown jewel of the Westminster parliamentary tradition. That one may hold and express opposing views while remaining fully committed to the political community is precisely what it means to be in loyal opposition to the Crown. ♛

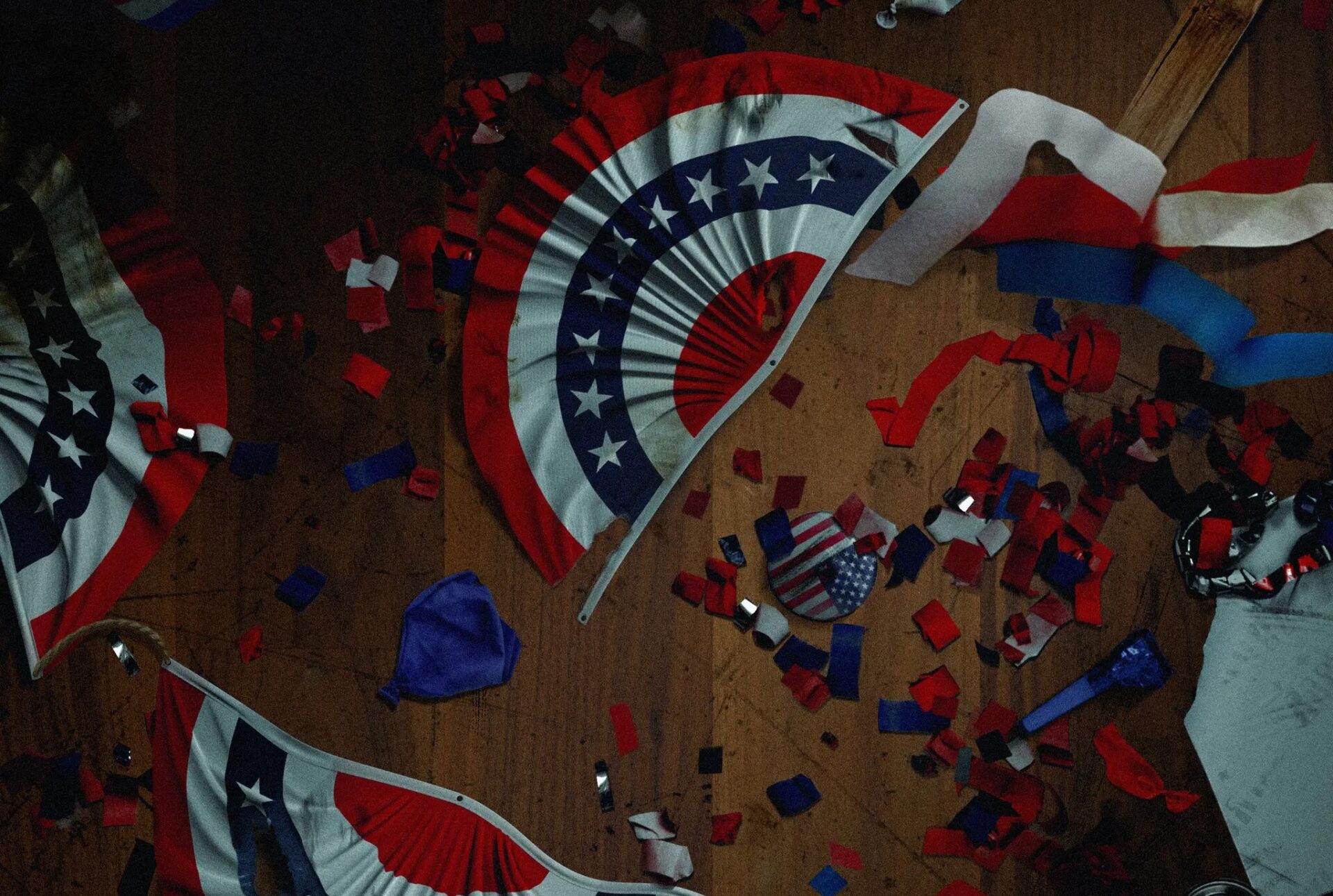

Cover image credit: Untitled conceptual photograph by Danielle Del Plato, first published in the New York Times on January 7, 2021.