Loyalist № 2

To the Peoples of North America, this being a Loyalist response to Federalist No. 2:

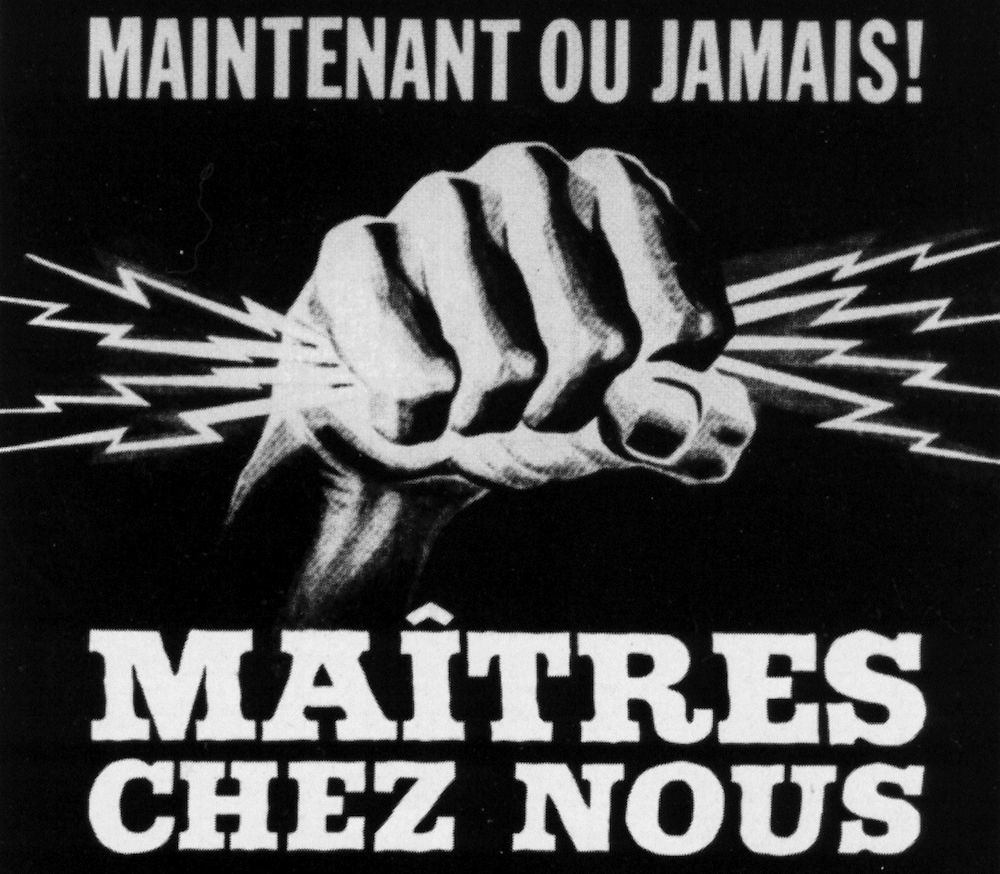

No. On June 12, 1990, Elijah Harper rose in the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba and, with that single utterance, began a filibuster blocking the assembly from considering the Meech Lake Accord, a set of proposed amendments to the Canadian Constitution. As he spoke, Harper, the only Indigenous member of the legislature, held an eagle feather, a symbol of spiritual strength in many First Nations cultures. Harper was standing against a pan-provincial consensus on constitutional reform that had taken Prime Minister Brian Mulroney three years to negotiate. Ten days later the ratification deadline expired. Harper had single-handedly killed Meech Lake.

The Accord aimed to bring Québec into the constitutional fold and address longstanding grievances about its autonomy and cultural recognition, issues rooted in its experience since Confederation in 1867. At Confederation, Québec and Ontario were created from the United Province of Canada, which had been formed in 1841 under British rule to assimilate French Canadians within a predominantly anglophone framework. Confederation divided the province, granting Québec provincial autonomy but leaving unresolved tensions over its unique identity within Canada.

The resulting ressentiment fuelled the sovereigntist movement, which picked up steam throughout the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s, the October Crisis of 1970, and culminated in the first Québec independence referendum in 1980. Notwithstanding the Québecois’ decisive rejection of independence in that vote, the sovereigntist movement was rejuvenated following the patriation of Canada’s Constitution in 1982, which Québec refused to sign at the time and continues to oppose even today.

Harper’s stand exposed for all the country to see that Québec’s alienation was not the only fracture in Canada’s federal framework. “We were to recognize Québec as a distinct society, whereas we as Aboriginal people were completely left out,” Harper said. “We were the First Peoples here – First Nations of Canada – we were the ones that made treaties with the settlers that came from Europe.” Harper’s act of resistance gave voice to an even deeper problem with the federation: the ongoing denial of Indigenous Peoples’ autonomy and inherent right to self-determination.

Writing in Federalist No. 2, John Jay argued for the adoption of the U.S. Constitution across the thirteen states on the basis that the American people had become a “band of brethren.”1 They had fought and died together in the War of Independence; they shared a common language, culture, and origin; and they had established deep political ties and common ideals with one another. For Jay, the need to establish a closer, more perfect Union had become obvious by 1787.

Modern Canada, on the other hand, has a far broader range of interests and identities compared to colonial America. The failure of the Meech Lake Accord was a reminder of just how difficult it has been for Canadians to reconcile Our differences. Our recent history has only made things more difficult in this respect with the fading of English Canada, the adoption of official bilingualism and multiculturalism, and Our evolution into an immigration society. Arguing against his own anti-federalist opponents, Jay writes,

It is well worthy of consideration, therefore, whether it would conduce more to the interest of the people of America that they should, to all general purposes, be one nation, under one federal government, than that they should divide themselves into separate confederacies, and give to the head of each the same kind of powers which they are advised to place in one national government.

Understanding that Canada stood at a similar crossroads in June 1990, Mulroney tried again. Two years later his government finalized the Charlottetown Accord, after consulting more broadly this time. Charlottetown was a much more ambitious attempt to repair Canada’s fractures. Its centerpiece was the “Canada Clause,” a sweeping statement of shared values like parliamentary democracy, the rule of law, and the rights of both individuals and communities. It recognized Québec as a distinct society and, for the first time, affirmed Indigenous Peoples’ inherent right to self-determination.

Somewhat like Jay’s vision of unity in Federalist No. 2, the Charlottetown Accord aimed to reimagine Canada not as a mere collection of provinces but as a diverse federation united in shared fundamental values. The Accord proposed a transformative new third order of government for Indigenous Peoples as equal partners in the federation, alongside the provincial and federal governments. It also envisioned a fully transformed Senate, more devolved powers to the provinces, complementary powers of taxation, and a guarantee of national standards for social programs like healthcare and education.

It was an ambitious vision – arguably more so than the unifying government Jay and his co-authors envisioned in the Federalist Papers. As Jay himself points out in Federalist No. 2, the challenge lay in finding the right balance between competing interests in order to safeguard the federation against degeneration into faction at the expense of the collective good.2 Yet despite unanimous support from the ten premiers, four national Indigenous organizations, and most major political parties, Canadian voters rejected the Charlottetown Accord 55 to 45 percent in a national referendum on October 26, 1992.

Calling the referendum had clearly been a mistake. Not only was it not a legal requirement to pass the agreed-upon amendments, but the deal was the product of years of hard work to find common ground between a multitude of competing interests. The problem with referendums on complex issues – Brexit being another particularly salient example – is that they are incapable of offering alternatives. Their verdicts are by nature non-negotiable and therefore final. Jay again:

If the people at large had reason to confide in the men of that [Continental] Congress, few of whom had been fully tried or generally known, still greater reason have they now to respect the judgment and advice of the [constitutional] convention, for it is well known that some of the most distinguished members of that Congress, who have been since tried and justly approved for patriotism and abilities, and who have grown old in acquiring political information, were also members of this convention, and carried into it their accumulated knowledge and experience.

Ordinary citizens could not reasonably have been expected to make an informed decision about whether to accept the Charlottetown Accord because, as Jay argues, they had not themselves been part of the complex discussions or even been privy to the reasons for compromises that had had to be made. On the contrary, the peoples of Canada had sent their representatives to do precisely that difficult work for them. And if they trusted those same leaders to govern their provinces and the country, they ought equally to have trusted their judgment to fix what was broken. Indeed, that point applies even more to Our Own case, considering that the proposed constitutional amendments at both Meech Lake and Charlottetown required full unanimity among the federation’s members.

That threshold was already a near-impossible bar to clear, ironically for the very same reasons that constitutional reform is needed in the first place, never mind the added burden of securing majority support in a national referendum. Not since the War of 1812 had We had to grapple – really grapple – with the meaning of Canadian identity and the fundamental purpose of Our federation. It is now generally agreed that constitutional reform in Canada is a fool’s errand, and none of the five Prime Ministers since Mulroney have tried or even suggested re-engaging with it. Yet with so many more outstanding divisive questions now accumulating, like the powers of municipalities and the role of the Crown, negotiating solutions to Our federation’s constitutional problems only gets more difficult with time. We ignore these fractures in Our federation at Our peril.

It has now been 33 years since the rejection of the Charlottetown Accord. Just as Jay asked his own compatriots 237 years ago, so too We must ask: will Canada be one or many? Jay argued that failure to ratify the U.S. Constitution “would put the continuance of the Union in the utmost jeopardy.” He concludes Federalist No. 2 by quoting the first line of Wolsey’s farewell speech from Shakespeare’s Henry VIII. In Canada’s case, perhaps the ending of that same speech is more appropriate:

That sweet aspect of princes, and their ruin,

More pangs and fears than wars or women have;

And when he falls, he falls like Lucifer,

Never to hope again. ♛

Cover image credit: The Death of General Wolfe at the Battle of the Plains of Abraham, painted by Benjamin West (1770).

Footnotes

- There would seem to be an echo here from a famous passage of Skakespeare’s St. Crispin’s Day Speech in Henry V:

“From this day to the ending of the world, / But we in it shall be rememberèd— / We few, we happy few, we band of brothers; / For he to-day that sheds his blood with me / Shall be my brother…”

The same passage lends the title to the HBO series. - The question of faction is discussed in greater detail in Federalist Nos. 9 and 10. We will take it up Ourselves in subsequent papers.

What role do you believe public sentiment plays in these discussions about constitutional ammendmentand has there every been widespread public suport in Canada for ammendments (whether the public knew the issue required this or not) that have not received political suport?

The best way to describe Canadian public sentiment on these questions might be “confused.” But even though the referendum on the Charlottetown Accord in 1992 killed the deal, public sentiment is still shaped by that rejection in indirect ways, as I’ve suggested with reference to the Idle No More movement. Beyond that, the two levels of government continue to fight over equalization and health funding transfers, jurisdiction over offshore resources like oil and gas remain points of tension, the western provinces feel alienated, Québec feels stifled. There are clear yet unresolved conflicts in the federation.

If the public better understood that constitutional reforms could be negotiated by elected officials to solve these problems, the voters would probably support a new deal on the constitution, almost no matter what the exact details of the final package of amendments might be. But, much like how we don’t elect the Prime Minister, it should be for the voters to decide these things indirectly during a general election.

We also shouldn’t underestimate the cultural influences of political norms to the south. Many state constitutions can only be amended by ballot measures. (Yet, interestingly, this does not apply to the U.S. Constitution.)