Loyalist № 5

To the Peoples of North America, this being a Loyalist response to Federalist No. 3:

Founding myths can rarely be traced to a single point of origin. They tend to emerge and develop organically over time based on such factors as culture, history, economic conditions – and political utility.1 The United States is fond of imagining itself to be the “indispensable nation,” meaning the one and only country to use its political, economic, and military might to build and maintain a just and rational world order. Secretaries of State from both parties – such as Madeleine Albright, Condoleezza Rice, and Hillary Clinton – have often used the term when speaking about American foreign policy.

We can trace, if not the exact origins of the myth itself, then at least some of its very early seeds. In Federalist No. 3, written in 1787, John Jay makes a particular kind of argument for the utility of forming a stronger Union of the states. He rightly points out that the first and most essential function of any national government must be to ensure the safety of the people against foreign powers. (The need, likewise, for safety against domestic dangers is noted but is considered later in the Federalist Papers.)

Jay pursues the theme methodically. What are the types and causes of danger from foreign powers? Conflict with other countries, he reasons, arise for both just and unjust reasons, and can be “provoked or invited.” According to Jay, the framing of the U.S. Constitution minimizes these risks to the safety of the Union in three distinct but related ways.

First, and most obviously, a national government will be able to stand against foreign threats more effectively than any of the individual states would be able to on their own. Jay writes,

It is well known that acknowledgments, explanations, and compensations are often accepted as satisfactory from a strong united nation, which would be rejected as unsatisfactory if offered by a State or confederacy of little consideration or power.

This point implies that the national government will need to build a strong military for the purposes of credibility and deterrence. The combined military power of the states will help the Union to avoid inviting unjust conflict upon itself while at the same time ensuring appropriate preparedness should the use of force become necessary in a justified conflict.

Second, a national government is better able to moderate the passions and self-interest that tend to spur lesser leaders to act in ways that do not necessarily serve the collective interests of the people. Jay reasons that state governments are by nature more responsive to the local demands and preferences of the people and are therefore more susceptible to making incorrect or unreasonable decisions if left to themselves. A national government, on the other hand, is by nature more distant; it will therefore possess “wisdom and prudence [that] will not be diminished by the passions which actuate the parties most immediately interested.” A stronger Union is therefore less likely to provoke unjust conflict with foreign powers.

Third, Jay believes that a national government is more likely to attract the most qualified leaders simply because the combined population of the states means that the electorate will have a wider field of candidates from which to choose. Conversely, Jay also believes the greater eminence, dignity, and honour of high office will likewise entice the most capable candidates to seek it:

The best men in the country will not only consent to serve, but also will generally be appointed to manage it; for, although town or country, or other contracted influence, may place men in State assemblies, or senates, or courts of justice, or executive departments, yet more general and extensive reputation for talents and other qualifications will be necessary to recommend men to offices under the national government – especially as it will have the widest field for choice, and never experience that want of proper persons which is not uncommon in some of the States.

In other words, the superior competence and capabilities of the national government will attract strong leadership, thereby reducing the risk of just wars being fought against the United States while also disinclining the United States from engaging in unjust wars against foreign powers.

All told, Jay’s argument boils down to his conviction that the U.S. Constitution establishes a “national government [that is] more wise, systematical, and judicious than those of individual States, and consequently more satisfactory with respect to other nations, as well as more safe with respect to us.” There is a clear line of thought building here from the first two Federalist Papers that providence has afforded the Founders – who are “highly distinguished by their patriotism, virtue and wisdom”2 – the exceptional if not divine opportunity to decide, through reason alone, how Americans may best govern themselves.

This view is now referred to as American exceptionalism; or, in President Ronald Reagan’s phrasing, “the shining city upon a hill” that serves as a beacon for all the world. It is barely a hop, skip, and a jump to the idea that American power can and should be projected across the world to safeguard peace while also promoting democratic principles. Motivated by its own founding myths, the United States mobilized the “Arsenal of Democracy” in World War II to save the United Kingdom from Hitler and defeat fascism, to rebuild Europe afterwards, and then to establish much of what we now know as the “rules-based” international order best exemplified by the United Nations, the North Atlantic alliance (NATO), and other multilateral institutions. That the United States also largely assumed the role of enforcing those same international rules, sometimes through deterrence and other times through direct military action, did indeed tend to make it the “indispensable nation.”

John Jay would surely have agreed that these things made the United States safer because they made the whole world safer. Yet history also clearly shows that the Framers underestimated the extent to which the United States would arm itself and, at the same time, overestimated the ability of the national government to act with reason and restraint. The Massacre at Wounded Knee in 1891; the takeover of the Philippines in 1899; the overthrow of Prime Minister Mosaddeq in Iran in 1953; the carpet-bombing of Southeast Asia in 1969-73; the unprovoked invasion of Iraq in 2003 – the list goes on. In all of these cases, unmoderated passions and a thirst for military conquest circumvented the Constitution that was intended to keep them in check.3

At the same time, the United States has time and again failed to live up to the democratic principles it loudly proclaims. The Clinton Administration failed to intervene in the Rwandan genocide in 1994. The Bush II Administration disappeared and tortured untold numbers at CIA Blacksites post-9/11 and onwards. The Obama Administration retreated from its “red line” on Bashar al-Assad’s use of chemical weapons against civilians in Syria in 2012. The first Trump Administration wilfully separated hundreds of migrant children from their parents at the southern border with Mexico, many never to be reunited. Under his second administration President Trump berated Volodymyr Zelenskyy, the elected President of Ukraine and leader of an existential battle against Russia for the democratic soul of his country. In all of these cases, America abandoned the principles that are supposed to distinguish it from other nations.

Foreign observers have long pointed out the gap between the values that America proclaims and what it actually puts into practice.4 Ordinary Americans, too, seem increasingly to be rejecting the idea that the United States occupies any special kind of place in the arc of history.

The argument of Federalist No. 3 imagined that a “more general and extensive reputation for talents and other qualifications will be necessary to recommend men to offices under the national government.” To this We can only observe that a twice-impeached convicted criminal who has radical ideas about neo-expansionism, a penchant for attacking democratic allies and praising authoritarian adversaries, and a clear intent to dismantle the rules-based international order that took nearly a century to build; now, this is the man occupying the same office as George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, and Franklin Delano Roosevelt. And he has been elected to that office not once, but twice.

Today’s America is not the one that John Jay imagined or hoped for. Perhaps, too, it is one that We and the rest of the democratic world would rather dispense with. ♛

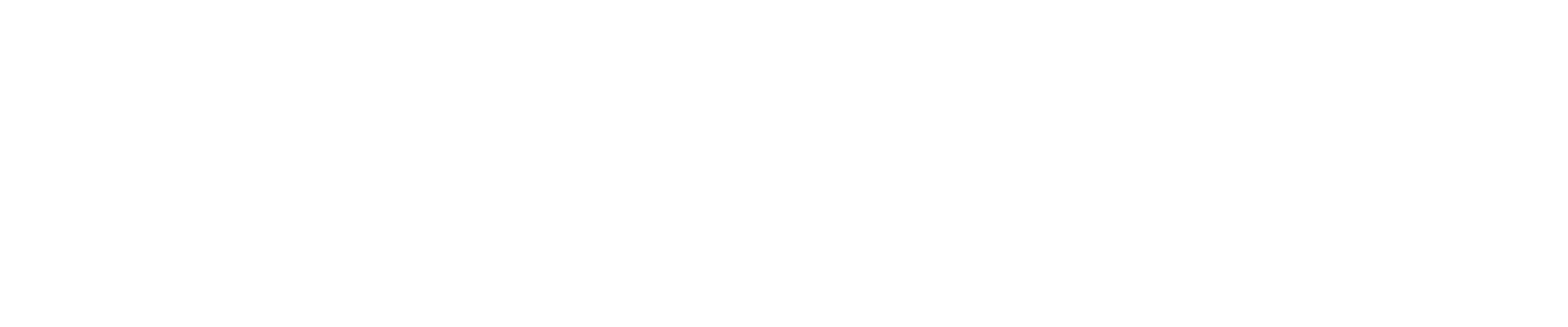

Cover image credit: Reversing Manifest Destiny, painted by by Charles Hillard for the Indian Land Tenure Foundation (date unknown).

Footnotes

- Myths are not necessarily true or false. They are merely stories We tell Ourselves to make sense of Our place in the world.

- See Federalist No. 1.

- This problem is no doubt exacerbated by the rise of the imperial presidency, which We will later explore in greater detail.

- See Foreign Policy, Boston University Today, and the Washington Post for some examples. For more of an economic perspective, see the Financial Post.