Loyalist № 6

To the Peoples of North America, this being a Loyalist response to Federalist No. 70:

How many members ought to make up the Presidency? The question may seem a strange one to ask in the context of twenty-first-century democracy. But in fact the idea, historically, is not all that unusual. Alexander Hamilton wanted to make the alternative – a unitary Presidency – common sense. Our reaction to the question he takes up in Federalist No. 70 shows that he succeeded.

Many long-established republics that existed at the time the Federalist Papers were written – like Switzerland (1291-1798), Venice (697-1797), and Genoa (1099-1797) – placed executive power in the hands of co-rulers, triumvirates, or ruling councils. The same arrangement was especially commonplace in early revolutionary democracies that had overthrown monarchies. Such was the case under the Commonwealth of England (1649-1660), the First French Republic (1792-1804), and the Batavian Republic in the Netherlands (1781-1795) – all short-lived.

That Alexander Hamilton devotes all of Federalist No. 70 to discussing whether the United States should adopt a unitary executive or a plural one indicates that the latter idea was at some point seriously considered by the Framers. Hamilton argues strongly against it, citing the absolute necessity of a unitary executive’s greater energy, efficiency, and accountability. Perhaps intending to model the virtues of the form of executive power he champions, Hamilton presents his arguments with exceptional economy (for the eighteenth century, at least).

As to energy:

A feeble Executive implies a feeble execution of the government. A feeble execution is but another phrase for a bad execution; and a government ill executed, whatever it may be in theory, must be, in practice, a bad government.

As to efficiency:

Decision, activity, secrecy, and despatch will generally characterize the proceedings of one man in a much more eminent degree than the proceedings of any greater number; and in proportion as the number is increased, these qualities will be diminished.

As to accountability:

It is far more safe there should be a single object for the jealousy and watchfulness of the people.

Pragmatist that he is, Hamilton reinforces his arguments with detours through classical history, and he briefly considers comparisons with cabinet government in the Westminster system. Despite the meandering, his bottom line is clear: good government calls for a decisive executive and the people need to know whom to support and whom to punish at the polls. Only a unitary office can achieve that. Had Hamilton’s argument not prevailed among the other Framers, a “First American Republic” (1789-1830?) may well have joined Our above list of short-lived revolutionary republics.

Imagine that the arguments of Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison were voted down at the Constitutional Convention in 1787. Instead of creating a unitary Presidency and Vice-Presidency, delegates approved a counterproposal to institute a five-member plural executive called the Council of the Republic. One member each would be elected from the Northern states, the Southern states, and the Western territories. Each would serve as Commander of the combined militias of their respective regions, the result of a compromise reached with skeptics who worried that vesting all military power in a single office of Commander-in-Chief would lead to dictatorship. The remaining two members of the Council of the Republic would be appointed, one each from the Senate and the House of Representatives. In an effort to promote consensus-building and cooperation, the Council of the Republic would choose a Chair from among its members.

Imagine further the composition of the Council of the Republic in early 1812. As intended, it reflects the young Republic’s varied regions and interests. James Madison, representing the South and serving as Chair, advocates for war with Britain to assert national sovereignty and protect Southern interests. DeWitt Clinton, the Northern member, opposes any war with Britain’s remaining continental colonies, expressing concern about the devastating impact it would have on Northern commerce. William Henry Harrison, the Western member, supports military action but demands greater resources to defend frontier settlements. Rufus King, the Senate appointee, stands for Northern Federalist opposition to the war, while Henry Clay, the House appointee, voices a passionate desire to finish the revolution that started in 1776 by expanding American territory westward and northward into Canada.

In an effort to outmanoeuvre the two Northern members, the three Southern members work directly with Congress to have it declare war on Britain, which Congress does in late spring of 1812. Yet even at the outset of hostilities, the Council struggles to adopt a coherent war strategy. Harrison’s Western militias, underfunded and poorly coordinated with Northern forces, suffer repeated defeats. At the Battle of the River Raisin in early 1813, British and Native American forces rout American troops, consolidating British control over the Michigan Territory. Harrison, enraged by the lack of support from Northern militias under Clinton’s authority, publicly accuses the Northern Commander of sabotaging the war effort.

In the Northeast, British forces advance into New York, capitalizing on Clinton’s reluctance to deploy Northern militias for offensive operations. Fort Niagara is lost and key parts of New York state come under British occupation. Clinton, prioritizing the defense of New York’s ports over a broader national strategy, refuses to cooperate with Madison and Clay’s push for a renewed invasion of Canada.

In August 1814, British forces under General Robert Ross march on Washington, after a decisive victory at the Battle of Bladensburg. With the Southern militias underfunded and poorly organized, Madison fails to mount an effective defense. The British torch the Capitol building and raze the city to the ground, delivering a humiliating blow to American morale. Harrison and Clinton blame Madison for prioritizing Southern coastal defences over protecting the seat of government. King, disgusted by the Council’s infighting, publicly advocates for a negotiated peace, while Clay doubles down on calls for renewed offensives in the West. Governors of the Northern states, feeling the economic effects of the conflict, begin openly questioning the utility of remaining in the Union.

By late 1814, British forces control significant portions of U.S. territory, including Michigan, parts of New York, and a string of forts along the Mississippi River. The British government, emboldened by American disunity, considers annexing parts of the West to head off further American expansion across North America. The Duke of Wellington, fresh from his victory over Napoleon, advises against outright annexation, wary of overextending British military power.

The Council of the Republic comes to see the necessity of ending the conflict but is unable to agree on a strategy for obtaining the most favourable terms from the British. Being more attuned to the public mood, Congress bypasses the paralyzed Council and sends a delegation to Montréal to sue for peace. The British agree to peace talks, but on condition that they take place in Washington, where they can further stoke American divisions. Amid the ruins of the U.S. capital, the British revel in the opportunity to display their renewed influence in North America.

Crippled by internal divisions, the Council of the Republic plays almost no role in the negotiations, which are driven largely by Congressional envoys. When the Treaty of Washington – popularly referred to as “the Burning Peace” – is finally signed in December 1814, it restores the pre-war boundaries but leaves many issues unresolved. The treaty fails to address Native American resistance or British interference in American affairs, which fuels resentment among Southern and Western leaders, who now see the war as a wasted opportunity.

The Northern states, devastated by the wartime blockade and bitter over the economic toll, convene the Hartford Convention in 1814. Clinton and King, though still nominally part of the Council of the Republic, support demands for constitutional amendments to reduce Southern and Western influence, seeing this as a way to avoid a replay of the failed war. The more radical delegates propose secession, arguing that the failures of the Council of the Republic have rendered federal authority illegitimate.

By 1820, Southern leaders like John C. Calhoun are pushing for a confederation of slave-holding states, while Northern states move to form an independent economic bloc protected by tariffs levied against the other states. Harrison, disillusioned by the government’s inability to secure the frontier, now leads a coalition of Western leaders advocating for autonomy. Regional militias clash as they increasingly try to assert direct control over their own territories, further weakening federal authority.

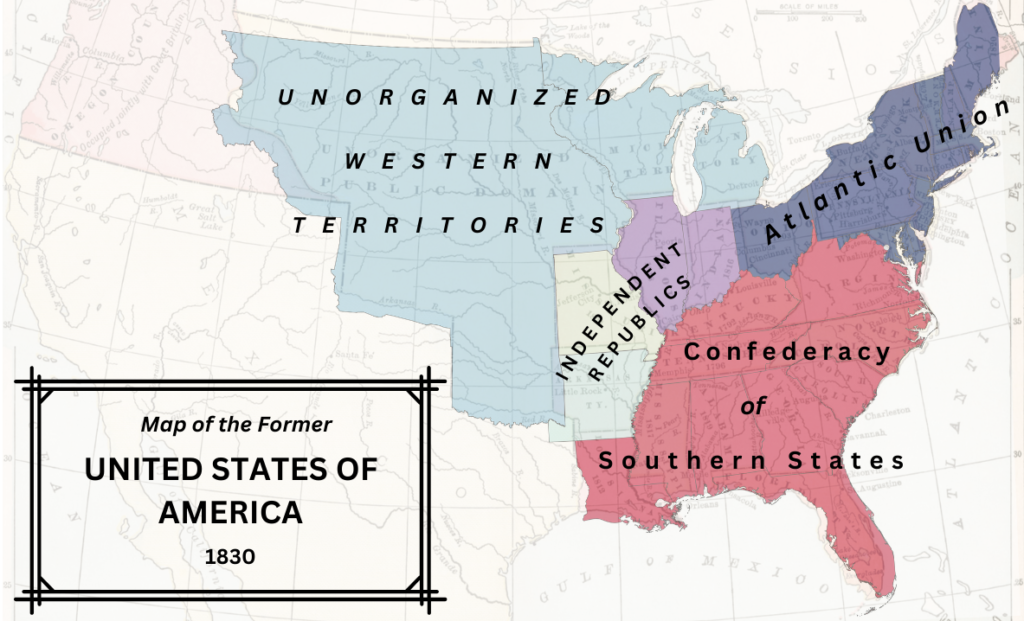

The election of 1824 is highly contested. It returns a deadlocked Council that is unable to reach agreement on its own Chair. Frustrated by federal dysfunction, South Carolina declares independence and urges its Southern neighbours to band together in a Confederation of Southern States. Northern states respond by organizing the Atlantic Union, while the Western territories become fragmented into smaller independent republics. Amid the confusion and chaos, the Council of the Republic eventually ceases to meet altogether and its members retreat to their respective regions.

Of course, history did not unfold in this way for the American Republic. The Framers got it right. From many interests, one country; from many votes, one President. E pluribus unum. ♛

Cover image credit: World War I propaganda poster, from the Smithsonian Institution (1917-18)

Worth noting that Switzerland STILL places executive power in the hands of co-rulers, seven to be precise.

Counterfactuals are fun though!